You don’t have to look hard to find medically trained folk who’ve become writers. Doctors Anton Chekhov, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Richard Gordon, Michael Crichton, Khaled Hosseini, Adam Kay and Freida McFadden to name a few. Even the world’s most successful crime writer with estimated sales of 2 billion books, Agatha Christie, was medical (a pharmacy dispenser). I’m in good company as a retired Scottish GP writing novels about medical women battling danger, dodgy doctors and disappearing patients in the patriarchal world of medicine. So, why I wonder, do so many medics write, often very successfully?

Granted literature has geniuses who without personal experience, can write about pretty well almost anything using research and professional advisors. Yet when writing medical or crime novels, us medics must be at an advantage. We can authentically portray medical settings and jargon and have knowledge of poisons and potentially undetectable means of ‘body despatch’ for plots. Perhaps even most importantly, we’ve had the advantage of unique doctor-patient consultations. Since Hippocratic times, patients anxious to stave off the Grim Reaper offer uber-frank information about emotions and feelings and our teaching allows us to plumb the depths of the human psyche thus exposed. Revelations about thousands of situations and relationships in consultations must aid us in novel character and plot development. Arguably, the motivations of bean-spilling clients in confidential legal interviews differs as lawyers seek more fact-based testimony, but they must also learn much of the human condition. Many lawyers also write e.g. Kafka, Grisham and Kirstin Hannah.

Over thirty years as a family doctor I’ve been privileged to hear thousands of patients’ stories whether surprising, enlightening, funny, sad or horrifying. More than once I’ve thought them unbelievable. Fact can indeed be stranger than fiction. Lord Byron thought so. His poem Don Juan (1824) suggests putting more fact into novels would better ‘show mankind their souls’ antipodes.’ And dark these hidden souls can be. As I’ve discovered, writing villains is more fun!

Beyond the consultation room, we docs revolve through hospital clinics, meetings, teaching, interacting with colleagues in multiple disciplines and encountering rudeness, devious pompous colleagues, prejudice, blunders and unexpected consequences. Excellent for plots! Other workplaces doubtless have similar, but medicine has an edge: day on day dramas of life, death and grief with all human life exposed – emotions, relationships, pain and panic. A perfect training ground for the novelist. Personally, I have a moral disquiet about memoirs revealing specifics (and a fear of lawsuits), yet Oliver Sacks and others have produced surprisingly detailed case histories.

But while voices and experience fed into my writing, it was a 2003 sabbatical year at Oxford University which made me objective enough to write candidly about medicine. Studying for a Medical Anthropology Masters assessing medical beliefs and practices across the world and in history to inform new avenues for health promotion, I discovered the ‘medicine’ I knew was only a construct. Patients ‘culturally’ present symptoms to ‘fit’ diseases doctors have invented. Diseases are named only to aid discussions of treatment and can change depending on cultures and era e.g. the patient alluding to evil spirits in the UK has Schizophrenia. In Kenya? It’s normal. Or the fainting Victorian girl’s diagnosis of ‘Chlorosis’? Lost in time. I graduated, my tutor satisfied, suitably ‘deconstructed!’

In retirement I drafted a medical novel exposing women’s inequality in hospital medicine. Finding it hard, I took university creative writing courses and discovered such niceties as characterisation, pace, dialogue, the essential art of ‘showing’ not ‘telling,’ and how to brutally edit by ‘murdering my darlings’ (first advised in 1914 by Arthur Quiller Couch). My novel theme switched to medical students in the sixties on prompts by my fellow course undergrads. How did we socialise without cell phones? Research without Google? Have sex without the pill?

So, book one became Not The Life Imagined, a rollercoaster tale of surviving life as a med student and junior doctor in sixties and seventies Glasgow. Its villain, Conor, epitomises everything you wouldn’t want a surgeon to be.

Book Two, Not The Deaths Imagined, has the same character, Beth, now a GP putting her family in peril as she attempts to whistle blow about a possible serial killer colleague. Murder just crept in but then, don’t docs know how death happens, and research shows that readers love a good murder?

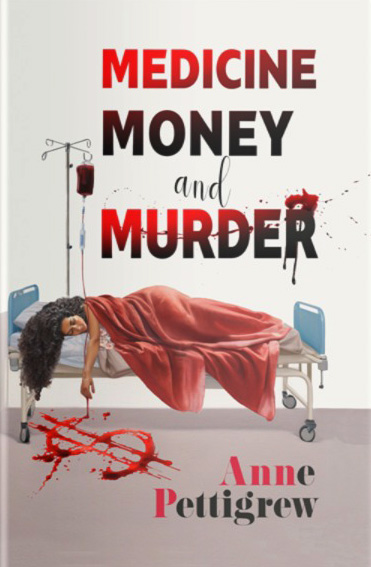

My third medical thriller (out September 2024, Sparsile Publishing) is Medicine, Money and Murder. Female Glasgow med students in a 1971 US hospital placement find blackmail, disappearing patients and murder. A salutary warning against privatizing the NHS…

Not sure about the motives of other medical authors but mine was primarily to record the multiple barriers women medics faced long before #MeToo since women doctors were largely absent from literature except as tokens or historical figures. I also wanted to show how the General Medical Council tenets of care, compassion, competence, trust and sexual propriety can be subverted. Sometimes easily. Not all medics are altruistic.

Mostly though, I wanted to entertain with a rollercoaster story involving humour, a touch of romance plus student antics from naïve days past and a murder or three. Like Michael Crichton, I’m happy to be considered a holiday ‘read’ though pleased my themes have engendered book club interest.

In short, Medicine, Writing and Murder lead easily into one another. And Medicine, Money and Murder? Heck, they do too…

(First published on https://www.booksbywomen.org on September 23rd 2024),

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.